Más idiomas

Más acciones

mSin resumen de edición |

mSin resumen de edición |

||

| (No se muestra una edición intermedia del mismo usuario) | |||

| Línea 9: | Línea 9: | ||

== Vida == | == Vida == | ||

=== Orígenes | === Orígenes, familia e infancia === | ||

Marx nació el 5 de mayo de 1818 en | Marx nació el martes 5 de mayo de 1818 a las 2 de la madrugada en Tréveris, hijo de [[Heinrich Marx]] (1777-1838) y de su esposa [[Henriette Presburg]] (1788-1863).<ref name=":1">{{Referencia|author=Michael Heinrich|year=2021|title=Karl Marx y el nacimiento de la sociedad moderna. Biografía y desarrollo de su obra. Volumen 1: 1818-1841|publisher=Akal|lg=http://books.ms/main/436FDDE5C350B4696059223010191902|trans-title=Karl Marx und die Geburt der modernen Gesellschaft: 1818-1841}}</ref> Fue el tercer hijo del matrimonio, habiendo nacido luego de Mauritz (1815-1819) y Sophie (1816-1886). A su vez, le sucedieron otros seis hermanos: Hermann (1820-1842), Henriette (1820-1845), Louise (1821-1893), Emilie (1822-1888), Caroline (1824-1847) y Eduard (1826-1837).<ref name=":1" /> En 1847, para cuando Marx había alcanzado la edad de 29 años, la mayoría de sus hermanos habían muerto de tuberculosis, excepto tres de sus hermanas, que finalmente le sobrevivieron: Sophie, Emilie y Louise .<ref name=":1" /> | ||

La familia de Karl Marx perteneció a una próspera pequeña burguesía de Tréveris, y | Tréveris era una pequeña ciudad rural, en el sur de la Prusia renana, actual Alemania, ubicada cerca de la frontera con Francia. Entre 1794 y 1815 había formado parte de Francia, hasta que, tras la derrota de Napoleón, la tegión fue anexada a Prusia.<ref>{{Referencia|author=Michael Heinrich|year=2019|title=Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work|page=39-40|quote=In 1794, Trier was occupied by French troops. Revolutionary France had not only beaten back the monarchist powers but had made considerable territorial conquests. [...] After Napoleon’s failed Russian campaign, French rule ended. In 1815, at the Congress of Vienna, Catholic Trier, along with the Rhineland, was awarded to Protestant Prussia.|city=Nueva York|publisher=Monthly Review Press|isbn=978-1-58367-735-3|lg=http://libgen.rs/book/index.php?md5=CE9645B504370175EDDFD48581F413A6}}</ref> En aquella época, Tréveris tenía aproximadamente 11,000 habitantes.<ref>{{Referencia|author=Michael Heinrich|year=2019|title=Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work|page=39-40|quote=In 1819, Trier had hardly more than 11,000 inhabitants; furthermore, about 3,500 soldiers were stationed in Trier (Monz 1973: 57). This was not an especially large population, even if one takes into consideration that back then most people lived in the countryside and cities had far fewer inhabitants than today. [...] The Trier in which Marx grew up was characteristically rural; it had only two main streets, the rest of the town consisting of side alleys and little streets.|city=Nueva York|publisher=Monthly Review Press|isbn=978-1-58367-735-3|lg=http://libgen.rs/book/index.php?md5=CE9645B504370175EDDFD48581F413A6}}</ref> | ||

La familia de Karl Marx perteneció a una próspera pequeña burguesía de Tréveris, y tenía orígenes judíos tanto por parte de su madre como de su padre, aunque su familia se convirtió al cristianismo protestante en 1824.<ref>{{Referencia|author=Michael Heinrich|year=2019|title=Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work|page=35|quote=Parents Heinrich (1777–1838) and Henriette (1788–1863) had married in 1814. Both came from Jewish families that converted to Protestant Christianity. Karl Marx was baptized on August 26, 1824, along with his then six siblings. At this point, his father had already been baptized; the exact date, however, is not known. His mother was baptized a year later, on November 20, 1825. On the occasion of the baptism of her children, according to the entry in the church register, she wanted to wait with her own baptism out of consideration for her still-living parents, but she wanted her children to be baptized.|city=Nueva York|publisher=Monthly Review Press|isbn=978-1-58367-735-3|lg=http://libgen.rs/book/index.php?md5=CE9645B504370175EDDFD48581F413A6}}</ref> El padre de Karl, Heinrich, era un abogado acomodado que gozaba de buena reputación entre los sectores más altos de la sociedad de Tréveris, y había acumulado un cierto nivel de riqueza.<ref>{{Referencia|author=Michael Heinrich|year=2019|title=Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work|page=35-42|quote=Marx’s father was a well-regarded lawyer in Trier, and his income allowed his family a certain affluence. Both the house on Brückengasse (today Brückenstraße), which the family rented and in which Karl was born,16 as well as the somewhat smaller, but centrally located house on Simeonstraße that the family purchased in the autumn of 1819 and in which young Karl grew up, were among the better bourgeois homes of the city. (p.35) | |||

[...] | [...] | ||

The center of social life in Trier was the Literary Casino Society (Literarische Casinogesellschaft) founded in 1818. Its statutes determined its purpose to be “maintaining a reading society connected to an association location for the convivial enjoyment of educated people” (quoted in Kentenich 1915: 731). In the Casino building, completed in 1825, there was a reading room that also contained several foreign newspapers. Balls and concerts, and on special occasions banquets, were regularly held (see Schmidt 1955: 11ff.). The sophisticated bourgeois stratum and the officers of the garrison belonged to the Casino. Karl’s father, Heinrich Marx, was one of the founding members. Similar societies, often with the same name, also arose at the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth century in other German cities; they were important focal points for the emerging bourgeois culture. Critique of existing political conditions was also articulated here. (pp. 41-42)|city=Nueva York|publisher=Monthly Review Press|isbn=978-1-58367-735-3|lg=http://libgen.rs/book/index.php?md5=CE9645B504370175EDDFD48581F413A6}}</ref><ref>{{Referencia|author=Michael Heinrich|year=2019|title=Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work|page=67-68|quote=Professional success was also reflected in a certain level of affluence. In 1819, Heinrich Marx was able to buy a house on Simeonstraße. According to the tax information evaluated by Herres, Heinrich Marx was assessed in 1832 as having an income of 1,500 talers annually, thus belonging to the upper 30 percent of the Trier middle and upper class that had a yearly income of more than 200 talers. Since this middle and upper class only comprised around 20 percent of the population, the Marx family, in terms of income, belonged to the upper 6 percent of the total population. With this income, the family was also able to accumulate a certain level of wealth, owning multiple plots of land used for agriculture, among which were vineyards. For wealthy citizens of Trier, ownership of vineyards was a popular retirement provision. The Marx family also employed servants. In the year 1818, there was at least one maid; for the years 1830 and 1833, “two maids” are documented.|city=Nueva York|publisher=Monthly Review Press|isbn=978-1-58367-735-3|lg=http://libgen.rs/book/index.php?md5=CE9645B504370175EDDFD48581F413A6}}</ref> | The center of social life in Trier was the Literary Casino Society (Literarische Casinogesellschaft) founded in 1818. Its statutes determined its purpose to be “maintaining a reading society connected to an association location for the convivial enjoyment of educated people” (quoted in Kentenich 1915: 731). In the Casino building, completed in 1825, there was a reading room that also contained several foreign newspapers. Balls and concerts, and on special occasions banquets, were regularly held (see Schmidt 1955: 11ff.). The sophisticated bourgeois stratum and the officers of the garrison belonged to the Casino. Karl’s father, Heinrich Marx, was one of the founding members. Similar societies, often with the same name, also arose at the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth century in other German cities; they were important focal points for the emerging bourgeois culture. Critique of existing political conditions was also articulated here. (pp. 41-42)|city=Nueva York|publisher=Monthly Review Press|isbn=978-1-58367-735-3|lg=http://libgen.rs/book/index.php?md5=CE9645B504370175EDDFD48581F413A6}}</ref><ref>{{Referencia|author=Michael Heinrich|year=2019|title=Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work|page=67-68|quote=Professional success was also reflected in a certain level of affluence. In 1819, Heinrich Marx was able to buy a house on Simeonstraße. According to the tax information evaluated by Herres, Heinrich Marx was assessed in 1832 as having an income of 1,500 talers annually, thus belonging to the upper 30 percent of the Trier middle and upper class that had a yearly income of more than 200 talers. Since this middle and upper class only comprised around 20 percent of the population, the Marx family, in terms of income, belonged to the upper 6 percent of the total population. With this income, the family was also able to accumulate a certain level of wealth, owning multiple plots of land used for agriculture, among which were vineyards. For wealthy citizens of Trier, ownership of vineyards was a popular retirement provision. The Marx family also employed servants. In the year 1818, there was at least one maid; for the years 1830 and 1833, “two maids” are documented.|city=Nueva York|publisher=Monthly Review Press|isbn=978-1-58367-735-3|lg=http://libgen.rs/book/index.php?md5=CE9645B504370175EDDFD48581F413A6}}</ref> | ||

=== Educación formal === | |||

=== | ==== Instituto Friedrich Wilhelm de Tréveris (1830-1835) ==== | ||

A los doce años, Marx fue admitido en el Instituto (''Gymnasium'') Friedrich Wilhelm de Tréveris para iniciar, en el semestre de invierno de 1830-1831, el cuarto curso del ciclo inferior de secundaria.<ref name=":1" /> No se sabe con certeza si antes de ingresar al instituto secundario (''Gymnasium'') de Tréveris, Marx hubiese asistido a alguna escuela primaria.<ref name=":1" /> Debido a que las escuelas primarias no eran muy buenas y que Marx fue admitido directamente en el instituto, es probable que recibiera clases privadas hasta entonces.<ref name=":1" /> El librero Eduard Montigny mencionó en una carta dirigida a Marx en 1848, que le había enseñado a escribir.<ref name=":1" /> | |||

El Friedrich Wilhelm Gymnasium, que en aquella época solo admitía alumnos varones, era una escuela pública de educación secundaria que preparaba a los estudiantes para la universidad.<ref name=":1" /> Los exámenes escritos para obtener el título de bachillerato superior (''Abitur'') en agosto de 1835 son los textos más antiguos de Marx que se conservan.<ref name=":1" /> Estos exámenes incluyen traducciones del alemán al francés, del griego clásico al alemán, y del alemán al latín, así como un examen presencial final de matemáticas y tres redacciones: una en latín, una en alemán y otra sobre religión.<ref name=":1" /> | |||

Durante este período formativo temprano, Marx estudió con varios profesores, algunos de los cuales eran críticos con el estado político de las cosas, entre ellos [[Johann Hugo Wyttenbach]], el director de la escuela.<ref>{{Referencia|author=Michael Heinrich|year=2019|title=Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work|page=97|quote=The towering presence of the Trier gymnasium was its director of many years, Johann Hugo Wyttenbach (1767–1848). He was also an archaeologist and founder of the Trier city library. In 1804, Wyttenbach was already director of the French secondary school; he remained director of the gymnasium until 1846. His thinking was strongly influenced by the Enlightenment; in his earlier years, he was an adherent of the French Jacobins. He maintained his liberal and humanistic ethos even under Prussian rule.|city=Nueva York|publisher=Monthly Review Press|isbn=978-1-58367-735-3|lg=http://libgen.rs/book/index.php?md5=CE9645B504370175EDDFD48581F413A6}}</ref><ref name=":0">{{Referencia|author=Michael Heinrich|year=2019|title=Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work|page=98-99|quote=When the young Karl started gymnasium in 1830, Wyttenbach was sixty-three years old. Most teachers were considerably younger, and as can be gleaned from the fragmentary information of the surviving records, at least a few of them had rather critical attitudes toward the reigning social and political conditions and were observed with distrust by the Prussian authorities. | |||

First and foremost to be named in this regard is Thomas Simon (1793– 1869), who taught French to Karl at the Tertia level. [...] He had “turned toward the concerns of the poor, neglected people,” since as a teacher he had seen daily that “it was not the possession of cold, filthy, minted money that makes a human being a human being, but rather character, disposition, understanding, and empathy for the weal and woe of one’s fellows” (quoted in Böse 1951: 11). In 1849, Simon was elected to the Prussian house of representatives, where he joined the left. His son, Ludwig Simon (1819–1872), also attended the gymnasium in Trier and took the Abitur exams a year after Karl. [Ludwig] was elected to the national assembly in 1848. As a result of his activities during the revolutionary years of 1848–49, the Prussian government brought multiple legal proceedings against him and convicted him in absentia to death, so that he had to emigrate to Switzerland. | First and foremost to be named in this regard is Thomas Simon (1793– 1869), who taught French to Karl at the Tertia level. [...] He had “turned toward the concerns of the poor, neglected people,” since as a teacher he had seen daily that “it was not the possession of cold, filthy, minted money that makes a human being a human being, but rather character, disposition, understanding, and empathy for the weal and woe of one’s fellows” (quoted in Böse 1951: 11). In 1849, Simon was elected to the Prussian house of representatives, where he joined the left. His son, Ludwig Simon (1819–1872), also attended the gymnasium in Trier and took the Abitur exams a year after Karl. [Ludwig] was elected to the national assembly in 1848. As a result of his activities during the revolutionary years of 1848–49, the Prussian government brought multiple legal proceedings against him and convicted him in absentia to death, so that he had to emigrate to Switzerland. | ||

| Línea 27: | Línea 31: | ||

Heinrich Schwendler (1792–1847), who taught French to Marx at the Obersekunda and Prima levels, was suspected in 1833 by the Prussian government of being the author of an insurgent leaflet; he was accused of “poor character” and of “familiar relationships to all the fraudulent minds of the local city.” In 1834, a ministerial commission warned of the “pernicious orientation” of Simon and Schwendler, and in 1835, the provincial school council regarded his dismissal as desirable, but could not find a sufficient reason (Monz 1973: 171, 178). | Heinrich Schwendler (1792–1847), who taught French to Marx at the Obersekunda and Prima levels, was suspected in 1833 by the Prussian government of being the author of an insurgent leaflet; he was accused of “poor character” and of “familiar relationships to all the fraudulent minds of the local city.” In 1834, a ministerial commission warned of the “pernicious orientation” of Simon and Schwendler, and in 1835, the provincial school council regarded his dismissal as desirable, but could not find a sufficient reason (Monz 1973: 171, 178). | ||

Johann Gerhard Schneeman (1796–1864) had studied classical philology, history, philosophy, and mathematics; he published numerous contributions on the archaeology of Trier. At the Tertia and Obersekunda levels, he taught Karl Latin and Greek. In 1834, Schneeman also participated in the singing of revolutionary songs at the Casino and was interrogated by the police as a result.|city=Nueva York|publisher=Monthly Review Press|isbn=978-1-58367-735-3|lg=http://libgen.rs/book/index.php?md5=CE9645B504370175EDDFD48581F413A6}}</ref> En esa época, el liberalismo se asociaba con ideales revolucionarias y un sentimiento romántico hacia la Revolución Francesa, ambos mal vistos por el gobierno prusiano. | Johann Gerhard Schneeman (1796–1864) had studied classical philology, history, philosophy, and mathematics; he published numerous contributions on the archaeology of Trier. At the Tertia and Obersekunda levels, he taught Karl Latin and Greek. In 1834, Schneeman also participated in the singing of revolutionary songs at the Casino and was interrogated by the police as a result.|city=Nueva York|publisher=Monthly Review Press|isbn=978-1-58367-735-3|lg=http://libgen.rs/book/index.php?md5=CE9645B504370175EDDFD48581F413A6}}</ref> Sus ideas eran ilustradas, y en su juventud había sido partidario de los jacobinos. Describió al instituto como una institución en la que los jóvenes "se formaban en la santa fe en el progreso y el ennoblecimiento". En un informe de 1818, se criticaba su trato con los estudiantes por ser demasiado cariñoso y poco riguroso. Sin embargo, protegía a sus profesores y soslayaba la exigencia de colaborar con las autoridades policiales. En esa época, el liberalismo se asociaba con ideales revolucionarias y un sentimiento romántico hacia la Revolución Francesa, ambos mal vistos por el gobierno prusiano.<ref name=":1" /> | ||

En cuanto a lo que a vida privada se refiere, durante esta etapa Marx tendría como compañero a Edgar von Westphalen quien inició simultáneamente con él los estudios en el Gymnasium. Este era a su vez el hermano de Jenny, futura esposa de Marx. En los primeros años de amistad entre Karl y Edgar probablemente la diferencia de edad de Jenny desempeñara un papel destacado. Cuando en 1831 esta estuvo prometida por un breve espacio de tiempo, ella tenía diecisiete años, y Karl, trece. Pero unos años después esta diferencia de edad fue perdiendo importancia. La familia von Westphalen también era una familia pequeñoburguesa.<ref>{{Referencia|author=Michael Heinrich|year=2019|title=Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work|page=45|quote=Ludwig von Westphalen and Heinrich Marx had annual incomes of 1,800 and 1,500 taler, respectively.|city=Nueva York|publisher=Monthly Review Press|isbn=978-1-58367-735-3|lg=http://libgen.rs/book/index.php?md5=CE9645B504370175EDDFD48581F413A6}}</ref> El joven Karl tenía una amistad con el barón Johann Ludwig von Westphalen, padre de Edgar y Jenny, y se convirtió en una influencia para Marx a través de su intercambio intelectual.<ref>{{Referencia|author=Michael Heinrich|year=2019|title=Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work|page=36|quote=Eleanor also discloses that the young Karl was intellectually stimulated primarily by his father and his future father-in-law, Ludwig von Westphalen. It was from the latter that he “imbibed his first love for the “Romantic” School, and while his father read him Voltaire and Racine, Westphalen read him Homer and Shakespeare.” The fact that Marx dedicated his doctoral dissertation rather emotionally to Ludwig von Westphalen in 1841 demonstrates how important the latter was to him.|city=Nueva York|publisher=Monthly Review Press|isbn=978-1-58367-735-3|lg=http://libgen.rs/book/index.php?md5=CE9645B504370175EDDFD48581F413A6}}</ref> | |||

==== Universidad de Bonn (1835-1836) ==== | ==== Universidad de Bonn (1835-1836) ==== | ||

Poco después de graduarse con un buen rendimiento en el Trier Gymnasium, Marx ingresó en la Universidad de Bonn el 17 de octubre de 1835, donde cursaría dos semestres. La familia Marx había elegido Bonn para la continuación de los estudios de Karl porque era la ciudad prusiana más cercana a Tréveris; ocho compañeros de bachillerato de Marx también terminaron estudiando allí. Karl estudiaría pues un primer año en Bonn, que estaba más cerca y era más barata, y luego se trasladaría a Berlín para acabar sus estudios en la mejor universidad de Prusia. | |||

En el formulario de solicitud de asistencia a clases, Marx se registró como ''studiosus iuris et cameralium'' (estudiante de derecho y cameralística). Los estudios de ''Kameralistik'' (Cameralística) en los siglos XVIII y XIX abarcaban economía, contabilidad y administración pública, una formación necesaria para los altos funcionarios. En esta época además, era común complementar los estudios con materias muy distintas, ya que el paso por la universidad tenía un carácter formativo. | |||

Marx se inscribió a nueve asignaturas diferentes para el primer semestre, a pesar de que su padre le recomendó no abarcar demasiado. Aunque realizó nueve pagos que le daban derecho a asistir y examinarse, tres de ellos aparecen tachados, lo que sugiere que asistió a pocas clases en esos casos. Las seis materias finalmente cursadas en cuestión corresponden a tres de la Facultad de Derecho ("Enciclopedia de la ciencia del derecho", con Eduard Puggé; "Instituciones", con Eduard Böcking; y "Historia del derecho romano", con Ferdinand Walter) y tres de la Facultad de Filosofía ("Mitología griega y romana", con Friedrich Gottlieb Welcker; "Nueva historia del arte", con Eduard d’Alton; y "Cuestiones en torno a Homero", con August Wilhelm von Schlegel). | |||

Para el segundo semestre, Marx nuevamente solicitó ser admitido en más clases de las que cursó, certificándose su asistencia a cuatro de ellas: "Historia del derecho alemán", con Ferdinand Walter; "Derecho internacional europeo" y "Derecho natural", con Eduard Puggé; y "Elegías de Sexto Propercio" con Schlegel. Durante su paso por Bonn, Marx adquirió una base sólida y buenos conocimientos de teoría del derecho, ya que tanto Puggé como Böcking habían estudiado en Berlín con Friedrich Carl von Savigny; siendo ambos eran representantes de la Escuela histórica del derecho. | |||

Marx fue presidente de la asociación lúdica de Tréveris en el semestre de verano de 1836. También recibió una pena de calabozo de un día por embriaguez y exceso de ruido. El padre de Marx desaprobaba la afición a la bebida y el estilo de vida de su hijo. | |||

A finales del segundo semestre se produce el compromiso entre Marx y Jenny. La versión más aceptada es que se comprometieron en secreto en el verano/otoño de 1836. Angelika Limmroth señala: "Cuando Karl había pasado un año en Bonn y volvió a Tréveris en el verano de 1836, el enamoramiento fue fulminante: la amistad juvenil se transformó en un amor tormentoso". Es evidente que Karl y Jenny se comprometieron, como tarde, en el verano de 1836, porque a partir de esa fecha Heinrich Marx (a quien la pareja le había confiado su secreto) empieza a hablar de Jenny y del compromiso en sus cartas. | |||

==== Universidad de Berlín (1836-1841) ==== | ==== Universidad de Berlín (1836-1841) ==== | ||

[[Archivo:Young_Marx.png|miniaturadeimagen|180x180px|Marx en 1839]] | |||

De Bonn se traslada Marx a Berlín donde se matricula el 22 de octubre de 1836 en la Facultad de Derecho. A diferencia de su tiempo en Bonn, Marx no se dedicó a los estudios con el mismo entusiasmo en Berlín. Aunque inicialmente mostró interés en la teoría del derecho, pronto se sintió más atraído por la filosofía terminando por especializarse en Historia y Filosofía. | |||

En una carta del 10 de noviembre de 1837, Marx comunicó a su padre dos cambios fundamentales en su vida: había dejado la poesía y adoptado la filosofía hegeliana. Durante una enfermedad, estudió a Hegel de principio a fin, lo que lo llevó a unirse a un "club de doctores" donde se debatían puntos de vista encontrados, encadenándolo cada vez más a la filosofía. En el "club de doctores", Marx conoció a amigos importantes para su desarrollo intelectual, como Adolf Friedrich Rutenberg, Karl Friedrich Köppen y Bruno Bauer. Rutenberg lo introdujo en el círculo, Köppen influyó en su interés por la historia y la mitología, y Bauer desempeñó un papel crucial en su adopción y desarrollo de la filosofía hegeliana. | |||

Marx se involucró en los debates en torno a la filosofía de Hegel, que eran comunes en la década de 1830. Se unió a los Jóvenes Hegelianos, un grupo de pensadores que criticaban la religión y la política desde una perspectiva hegeliana. La escuela hegeliana, promovida por el ministro de Cultura Altenstein, era una de las corrientes filosóficas más importantes en Alemania en ese momento. En aquella época, Marx era idealista hegeliano y pertenecía al círculo de los [[hegelianos de izquierda]], junto con Bruno Bauer y otros.<ref>[[Lenin]] (1914). ''Carlos Marx. (Breve esbozo biográfico, con una exposición del marxismo)'' [https://www.marxists.org/espanol/lenin/obras/1910s/carlos_marx/carlosmarx.htm marxists.org link]</ref> | |||

Marx enfrentó dificultades financieras durante su tiempo en Berlín, lo que pudo haber afectado su asistencia a cursos y su participación en la vida estudiantil. Fue denunciado varias veces ante los tribunales universitarios por sus acreedores. | |||

Durante su estancia en Berlín, Marx preparó su tesis doctoral, ''Diferencia entre la filosofía de la naturaleza de Demócrito y la de Epicuro''. Aunque estudió en Berlín, presentó su tesis en la Universidad de Jena en 1841, la cual no había visitado nunca y a donde tampoco se desplazó para doctorarse: se doctoró ''in absentia''. Las razones de esto no se conocen con certeza. | |||

=== Colonia y la ''Gaceta Renana'' (1842-1843) === | === Colonia y la ''Gaceta Renana'' (1842-1843) === | ||

| Línea 103: | Línea 128: | ||

<blockquote>''Véase también'': [[Portal:Obras de biblioteca de Karl Marx & Friedrich Engels]]</blockquote> | <blockquote>''Véase también'': [[Portal:Obras de biblioteca de Karl Marx & Friedrich Engels]]</blockquote> | ||

* '''1835''': ''[[Biblioteca:¿Se encuentra merecidamente el principado de Augusto entre las épocas más prósperas de la República romana?|¿Se encuentra merecidamente el principado de Augusto entre las épocas más prósperas de la República romana?]]'' | * ''Gymnasium'' de Tréveris: | ||

* '''1835''': ''[[Biblioteca:Reflexiones de un joven en la elección de una profesión|Reflexiones de un joven en la elección de una profesión]]'' | ** '''1835''': ''[[Biblioteca:¿Se encuentra merecidamente el principado de Augusto entre las épocas más prósperas de la República romana?|¿Se encuentra merecidamente el principado de Augusto entre las épocas más prósperas de la República romana?]]'' | ||

* '''1837''': ''[[Biblioteca:Carta al padre 1837|Carta al padre]]'' | ** '''1835''' ago. 10-16: ''[[Biblioteca:Reflexiones de un joven en la elección de una profesión|Reflexiones de un joven en la elección de una profesión]]'' | ||

* '''1837''': ''[[Biblioteca:Escorpión y Félix|Escorpión y Félix]]'' | * Universidad de Berlín: | ||

* '''1841''': ''[[Biblioteca:Diferencia de la filosofía de la naturaleza en Demócrito y en Epicuro|Diferencia de la filosofía de la naturaleza en Demócrito y en Epicuro]]'' | ** '''1837''' nov 10: ''[[Biblioteca:Carta al padre 1837|Carta al padre]]'' | ||

* '''1842''': ''[[Biblioteca:Observaciones sobre la reciente reglamentación de la censura prusiana|Observaciones sobre la reciente reglamentación de la censura prusiana]]'' | ** '''1837''': ''[[Biblioteca:Escorpión y Félix|Escorpión y Félix]]'' | ||

* '''1842''': ''[[Biblioteca:Contra el expolio de nuestras vidas|Contra el expolio de nuestras vidas]]'' (en la ''[[Gaceta Renana]]'') | ** '''1841''': ''[[Biblioteca:Diferencia de la filosofía de la naturaleza en Demócrito y en Epicuro|Diferencia de la filosofía de la naturaleza en Demócrito y en Epicuro]]'' | ||

* '''1842''': ''[[Biblioteca:Los debates sobre la Ley acerca del Robo de la leña|Los debates sobre la Ley acerca del Robo de la leña]]'' (en la ''[[Gaceta Renana]]'') | * Etapa pre-materialista | ||

* '''1843''': ''[[Biblioteca:Cartas a Ruge|Cartas a Ruge]]'' | ** '''1842''': ''[[Biblioteca:Observaciones sobre la reciente reglamentación de la censura prusiana|Observaciones sobre la reciente reglamentación de la censura prusiana]]'' | ||

* '''1844''': ''[[Biblioteca:Sobre la cuestión judía|Sobre la cuestión judía]]'' (en los ''[[Anuarios Franco-Alemanes]]'') | ** '''1842''': ''[[Biblioteca:Contra el expolio de nuestras vidas|Contra el expolio de nuestras vidas]]'' (en la ''[[Gaceta Renana]]'') | ||

* '''1844''': "Introducción" a la ''Contribución a la crítica de la filosofía del derecho de Hegel'' (en los ''[[Anuarios Franco-Alemanes]]'') | ** '''1842''': ''[[Biblioteca:Los debates sobre la Ley acerca del Robo de la leña|Los debates sobre la Ley acerca del Robo de la leña]]'' (en la ''[[Gaceta Renana]]'') | ||

* '''1844''': ''Crítica a la filosofía del Derecho Público (o del Estado) de Hegel'', también llamado ''Manuscrito de Kreuznach'' | ** '''1843''': ''[[Biblioteca:Cartas a Ruge|Cartas a Ruge]]'' | ||

* '''1844''': ''[[Biblioteca:Glosas marginales al artículo "El rey de Prusia y la reforma social. Por un prusiano"|Glosas marginales al artículo "El rey de Prusia y la reforma social. Por un prusiano"]]'' | * Surgimiento del materialismo dialéctico | ||

* '''1844''': ''Manuscritos económico-filosóficos de 1844'' | ** '''1844''': ''[[Biblioteca:Sobre la cuestión judía|Sobre la cuestión judía]]'' (en los ''[[Anuarios Franco-Alemanes]]'') | ||

* '''1845''': ''Tesis sobre Feuerbach'' | ** '''1844''': "Introducción" a la ''[[Biblioteca:Contribución a la crítica de la filosofía del derecho de Hegel|Contribución a la crítica de la filosofía del derecho de Hegel]]'' (en los ''[[Anuarios Franco-Alemanes]]'') | ||

* '''1845''': ''La sagrada familia'' (con [[Engels]]) | ** '''1844''': ''[[Biblioteca:Crítica a la filosofía del Derecho Público (o del Estado) de Hegel|Crítica a la filosofía del Derecho Público (o del Estado) de Hegel]]'', también llamado ''[[Biblioteca:Manuscrito de Kreuznach|Manuscrito de Kreuznach]]'' | ||

* '''1847''': ''La crítica moralizante y la moral crítica'' | ** '''1844''': ''[[Biblioteca:Glosas marginales al artículo "El rey de Prusia y la reforma social. Por un prusiano"|Glosas marginales al artículo "El rey de Prusia y la reforma social. Por un prusiano"]]'' | ||

* '''1847''': ''La miseria de la filosofía'' | ** '''1844''': ''[[Biblioteca:Manuscritos económico-filosóficos de 1844|Manuscritos económico-filosóficos de 1844]]'' | ||

* '''1848''': ''Manifiesto del Partido Comunista'' (con [[Engels]]) | ** '''1845''': ''[[Biblioteca:Tesis sobre Feuerbach|Tesis sobre Feuerbach]]'' | ||

* '''1849''': ''Trabajo asalariado y capital'' (en ''[[Nueva Gaceta Renana]]'') | ** '''1845''': ''[[Biblioteca:La sagrada familia|La sagrada familia]]'' (con [[Engels]]) | ||

* '''1850''': La lucha de clases en Francia (1848-1850) (en ''[[Nueva Gaceta Renana. Revista político-económica]]'') | ** '''1847''': ''[[Biblioteca:La crítica moralizante y la moral crítica|La crítica moralizante y la moral crítica]]'' | ||

* '''1850''': ''[[Biblioteca:Mensaje del Comité Central a la Liga de los Comunistas|Mensaje del Comité Central a la Liga de los Comunistas]]'' (con [[Engels]]) | ** '''1847''': ''[[Biblioteca:La miseria de la filosofía|La miseria de la filosofía]]'' | ||

* '''1852''': ''[[Biblioteca:El 18 brumario de Luis Bonaparte|El 18 de brumario de Luis Bonaparte]]'' | ** '''1848''': ''[[Biblioteca:Manifiesto del Partido Comunista|Manifiesto del Partido Comunista]]'' (con [[Engels]]) | ||

* '''1853''': ''[[Biblioteca:La dominación británica en la India|La dominación británica en la India]]'' | * Obras materialistas tempranas | ||

* '''1853''': ''[[Biblioteca:Futuros resultados de la dominación británica en la India|Futuros resultados de la dominación británica en la India]]'' | ** '''1849''': ''[[Biblioteca:Trabajo asalariado y capital|Trabajo asalariado y capital]]'' (en ''[[Nueva Gaceta Renana]]'') | ||

* '''1854-57''': ''[[Biblioteca:La España revolucionaria|La España revolucionaria]]'' | ** '''1850''': [[Biblioteca:La lucha de clases en Francia (1848-1850)|''La lucha de clases en Francia (1848-1850)'']] (en ''[[Nueva Gaceta Renana. Revista político-económica]]'') | ||

* '''1857''': '''[[Biblioteca:Grundrisse|''Elementos fundamentales para la crítica de la economía política'']] (''Grundrisse'')''' | ** '''1850''': ''[[Biblioteca:Mensaje del Comité Central a la Liga de los Comunistas|Mensaje del Comité Central a la Liga de los Comunistas]]'' (con [[Engels]]) | ||

* '''''[[Biblioteca:Contribución a la crítica de la ecomomía política|Una contribución a la crítica de la ecomomía política]]''''' | ** '''1852''': ''[[Biblioteca:El 18 brumario de Luis Bonaparte|El 18 de brumario de Luis Bonaparte]]'' | ||

** '''1853''': ''[[Biblioteca:La dominación británica en la India|La dominación británica en la India]]'' | |||

** '''1853''': ''[[Biblioteca:Futuros resultados de la dominación británica en la India|Futuros resultados de la dominación británica en la India]]'' | |||

** '''1854-57''': ''[[Biblioteca:La España revolucionaria|La España revolucionaria]]'' | |||

* Redacción de ''El Capital'' | |||

** '''1857-58''': '''[[Biblioteca:Grundrisse|''Elementos fundamentales para la crítica de la economía política'']] (''Grundrisse'') o Manuscrito de 1857-58''' | |||

** '''1859''': '''''[[Biblioteca:Contribución a la crítica de la ecomomía política|Una contribución a la crítica de la ecomomía política]]''''' | |||

** '''1861-63''': ''Manuscrito de 1861-63'' (Contiene ''Teorías de la plusvalía'') | |||

** '''1863-65''': Volumen 1 (perdido, excepto por el capítulo 6 "Resultados del proceso inmediato de producción" que permaneció inédito). Luego procede a escribir el Volumen 3 (Partes de la 1 a la 3), el Volumen 2, el Volumen 3 (Partes 4 a la 7). | |||

** '''1865''': ''[[Biblioteca:Salario, precio y ganancia|Salario, precio y ganancia]]'' | |||

** '''1867''': ''El Capital'' Vol. I | |||

* ''[[Biblioteca:Herr Vogt|Herr Vogt]]'' | * ''[[Biblioteca:Herr Vogt|Herr Vogt]]'' | ||

* ''[[Biblioteca:La guerra civil en USA|La guerra civil en USA]]'' (con Engels) | * ''[[Biblioteca:La guerra civil en USA|La guerra civil en USA]]'' (con Engels) | ||

Revisión actual - 00:50 6 feb 2025

Karl Marx | |

|---|---|

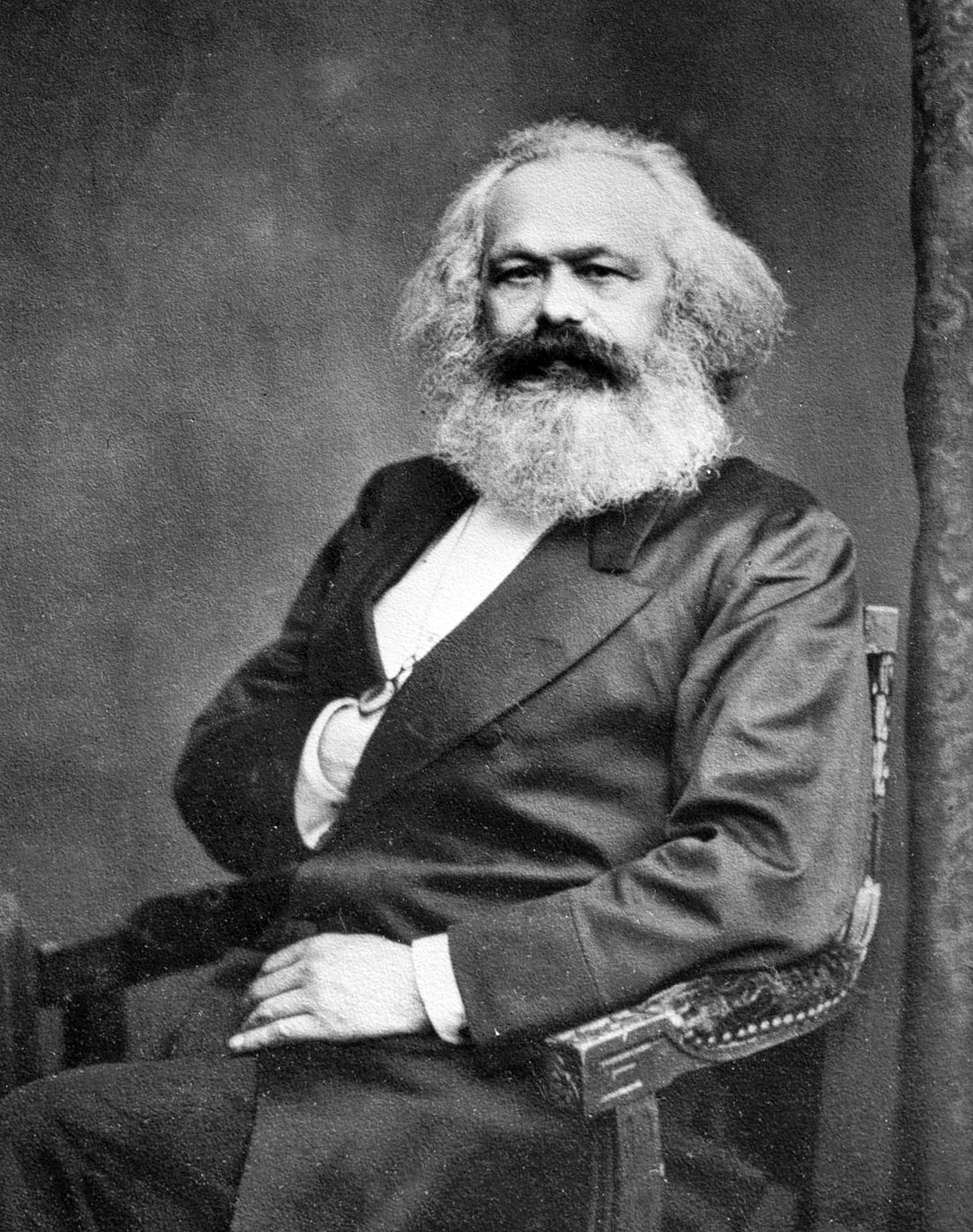

Retrato del camarada Marx | |

| Nació | Karl Heinrich Marx 5 de mayo de 1818 Tréveris, Reino de Prusia, Confederación Germánica |

| Murió | 14 de marzo de 1883 (64 años) Londres, Reino Unido |

| Nacionalidad | Prusa (1818–1845) Apátrida (después de 1845) |

| Conocido por | Desarrollando una línea de pensamiento político conocida como Marxismo |

| Campo de estudio | Filosofía, ciencia, economía política, historia |

Karl Heinrich Marx (Tréveris, Reino de Prusia; 5 de mayo de 1818 - Londres, Reino Unido; 14 de marzo de 1883), españolizado como Carlos Enrique Marx, fue un filósofo, economista, historiador, sociólogo, teórico político, periodista y revolucionario socialista alemán del siglo XIX. Es el pensador más importante del movimiento comunista.

Junto a su amigo y colaborador Friedrich Engels, descubrió las leyes del desarrollo de las sociedades humanas basándose en el método materialista dialéctico y creando así el Marxismo. Puso de relieve las contradicciones y la explotación intrínseca del capitalismo, y contribuyó a desarrollar modelos económicos socialistas. Sus obras más famosas, el Manifiesto Comunista, que escribió con Engels en 1848, y El Capital, cuyo primer volumen terminó en 1867, han tenido una enorme influencia internacional.

Las tradiciones intelectuales en las que Marx se inspiró principalmente fueron la filosofía alemana, la economía política inglesa y el socialismo francés.[1] Sus fuentes principales en la filosofía alemana fueron Hegel, Feuerbach, Bruno Bauer y Max Stirner; en la economía política inglesa Adam Smith y David Ricardo; y en el socialismo francés Henri de Saint-Simon, Charles Fourier y Robert Owen.

Vida[editar | editar código]

Orígenes, familia e infancia[editar | editar código]

Marx nació el martes 5 de mayo de 1818 a las 2 de la madrugada en Tréveris, hijo de Heinrich Marx (1777-1838) y de su esposa Henriette Presburg (1788-1863).[2] Fue el tercer hijo del matrimonio, habiendo nacido luego de Mauritz (1815-1819) y Sophie (1816-1886). A su vez, le sucedieron otros seis hermanos: Hermann (1820-1842), Henriette (1820-1845), Louise (1821-1893), Emilie (1822-1888), Caroline (1824-1847) y Eduard (1826-1837).[2] En 1847, para cuando Marx había alcanzado la edad de 29 años, la mayoría de sus hermanos habían muerto de tuberculosis, excepto tres de sus hermanas, que finalmente le sobrevivieron: Sophie, Emilie y Louise .[2]

Tréveris era una pequeña ciudad rural, en el sur de la Prusia renana, actual Alemania, ubicada cerca de la frontera con Francia. Entre 1794 y 1815 había formado parte de Francia, hasta que, tras la derrota de Napoleón, la tegión fue anexada a Prusia.[3] En aquella época, Tréveris tenía aproximadamente 11,000 habitantes.[4]

La familia de Karl Marx perteneció a una próspera pequeña burguesía de Tréveris, y tenía orígenes judíos tanto por parte de su madre como de su padre, aunque su familia se convirtió al cristianismo protestante en 1824.[5] El padre de Karl, Heinrich, era un abogado acomodado que gozaba de buena reputación entre los sectores más altos de la sociedad de Tréveris, y había acumulado un cierto nivel de riqueza.[6][7]

Educación formal[editar | editar código]

Instituto Friedrich Wilhelm de Tréveris (1830-1835)[editar | editar código]

A los doce años, Marx fue admitido en el Instituto (Gymnasium) Friedrich Wilhelm de Tréveris para iniciar, en el semestre de invierno de 1830-1831, el cuarto curso del ciclo inferior de secundaria.[2] No se sabe con certeza si antes de ingresar al instituto secundario (Gymnasium) de Tréveris, Marx hubiese asistido a alguna escuela primaria.[2] Debido a que las escuelas primarias no eran muy buenas y que Marx fue admitido directamente en el instituto, es probable que recibiera clases privadas hasta entonces.[2] El librero Eduard Montigny mencionó en una carta dirigida a Marx en 1848, que le había enseñado a escribir.[2]

El Friedrich Wilhelm Gymnasium, que en aquella época solo admitía alumnos varones, era una escuela pública de educación secundaria que preparaba a los estudiantes para la universidad.[2] Los exámenes escritos para obtener el título de bachillerato superior (Abitur) en agosto de 1835 son los textos más antiguos de Marx que se conservan.[2] Estos exámenes incluyen traducciones del alemán al francés, del griego clásico al alemán, y del alemán al latín, así como un examen presencial final de matemáticas y tres redacciones: una en latín, una en alemán y otra sobre religión.[2]

Durante este período formativo temprano, Marx estudió con varios profesores, algunos de los cuales eran críticos con el estado político de las cosas, entre ellos Johann Hugo Wyttenbach, el director de la escuela.[8][9] Sus ideas eran ilustradas, y en su juventud había sido partidario de los jacobinos. Describió al instituto como una institución en la que los jóvenes "se formaban en la santa fe en el progreso y el ennoblecimiento". En un informe de 1818, se criticaba su trato con los estudiantes por ser demasiado cariñoso y poco riguroso. Sin embargo, protegía a sus profesores y soslayaba la exigencia de colaborar con las autoridades policiales. En esa época, el liberalismo se asociaba con ideales revolucionarias y un sentimiento romántico hacia la Revolución Francesa, ambos mal vistos por el gobierno prusiano.[2]

En cuanto a lo que a vida privada se refiere, durante esta etapa Marx tendría como compañero a Edgar von Westphalen quien inició simultáneamente con él los estudios en el Gymnasium. Este era a su vez el hermano de Jenny, futura esposa de Marx. En los primeros años de amistad entre Karl y Edgar probablemente la diferencia de edad de Jenny desempeñara un papel destacado. Cuando en 1831 esta estuvo prometida por un breve espacio de tiempo, ella tenía diecisiete años, y Karl, trece. Pero unos años después esta diferencia de edad fue perdiendo importancia. La familia von Westphalen también era una familia pequeñoburguesa.[10] El joven Karl tenía una amistad con el barón Johann Ludwig von Westphalen, padre de Edgar y Jenny, y se convirtió en una influencia para Marx a través de su intercambio intelectual.[11]

Universidad de Bonn (1835-1836)[editar | editar código]

Poco después de graduarse con un buen rendimiento en el Trier Gymnasium, Marx ingresó en la Universidad de Bonn el 17 de octubre de 1835, donde cursaría dos semestres. La familia Marx había elegido Bonn para la continuación de los estudios de Karl porque era la ciudad prusiana más cercana a Tréveris; ocho compañeros de bachillerato de Marx también terminaron estudiando allí. Karl estudiaría pues un primer año en Bonn, que estaba más cerca y era más barata, y luego se trasladaría a Berlín para acabar sus estudios en la mejor universidad de Prusia.

En el formulario de solicitud de asistencia a clases, Marx se registró como studiosus iuris et cameralium (estudiante de derecho y cameralística). Los estudios de Kameralistik (Cameralística) en los siglos XVIII y XIX abarcaban economía, contabilidad y administración pública, una formación necesaria para los altos funcionarios. En esta época además, era común complementar los estudios con materias muy distintas, ya que el paso por la universidad tenía un carácter formativo.

Marx se inscribió a nueve asignaturas diferentes para el primer semestre, a pesar de que su padre le recomendó no abarcar demasiado. Aunque realizó nueve pagos que le daban derecho a asistir y examinarse, tres de ellos aparecen tachados, lo que sugiere que asistió a pocas clases en esos casos. Las seis materias finalmente cursadas en cuestión corresponden a tres de la Facultad de Derecho ("Enciclopedia de la ciencia del derecho", con Eduard Puggé; "Instituciones", con Eduard Böcking; y "Historia del derecho romano", con Ferdinand Walter) y tres de la Facultad de Filosofía ("Mitología griega y romana", con Friedrich Gottlieb Welcker; "Nueva historia del arte", con Eduard d’Alton; y "Cuestiones en torno a Homero", con August Wilhelm von Schlegel).

Para el segundo semestre, Marx nuevamente solicitó ser admitido en más clases de las que cursó, certificándose su asistencia a cuatro de ellas: "Historia del derecho alemán", con Ferdinand Walter; "Derecho internacional europeo" y "Derecho natural", con Eduard Puggé; y "Elegías de Sexto Propercio" con Schlegel. Durante su paso por Bonn, Marx adquirió una base sólida y buenos conocimientos de teoría del derecho, ya que tanto Puggé como Böcking habían estudiado en Berlín con Friedrich Carl von Savigny; siendo ambos eran representantes de la Escuela histórica del derecho.

Marx fue presidente de la asociación lúdica de Tréveris en el semestre de verano de 1836. También recibió una pena de calabozo de un día por embriaguez y exceso de ruido. El padre de Marx desaprobaba la afición a la bebida y el estilo de vida de su hijo.

A finales del segundo semestre se produce el compromiso entre Marx y Jenny. La versión más aceptada es que se comprometieron en secreto en el verano/otoño de 1836. Angelika Limmroth señala: "Cuando Karl había pasado un año en Bonn y volvió a Tréveris en el verano de 1836, el enamoramiento fue fulminante: la amistad juvenil se transformó en un amor tormentoso". Es evidente que Karl y Jenny se comprometieron, como tarde, en el verano de 1836, porque a partir de esa fecha Heinrich Marx (a quien la pareja le había confiado su secreto) empieza a hablar de Jenny y del compromiso en sus cartas.

Universidad de Berlín (1836-1841)[editar | editar código]

De Bonn se traslada Marx a Berlín donde se matricula el 22 de octubre de 1836 en la Facultad de Derecho. A diferencia de su tiempo en Bonn, Marx no se dedicó a los estudios con el mismo entusiasmo en Berlín. Aunque inicialmente mostró interés en la teoría del derecho, pronto se sintió más atraído por la filosofía terminando por especializarse en Historia y Filosofía.

En una carta del 10 de noviembre de 1837, Marx comunicó a su padre dos cambios fundamentales en su vida: había dejado la poesía y adoptado la filosofía hegeliana. Durante una enfermedad, estudió a Hegel de principio a fin, lo que lo llevó a unirse a un "club de doctores" donde se debatían puntos de vista encontrados, encadenándolo cada vez más a la filosofía. En el "club de doctores", Marx conoció a amigos importantes para su desarrollo intelectual, como Adolf Friedrich Rutenberg, Karl Friedrich Köppen y Bruno Bauer. Rutenberg lo introdujo en el círculo, Köppen influyó en su interés por la historia y la mitología, y Bauer desempeñó un papel crucial en su adopción y desarrollo de la filosofía hegeliana.

Marx se involucró en los debates en torno a la filosofía de Hegel, que eran comunes en la década de 1830. Se unió a los Jóvenes Hegelianos, un grupo de pensadores que criticaban la religión y la política desde una perspectiva hegeliana. La escuela hegeliana, promovida por el ministro de Cultura Altenstein, era una de las corrientes filosóficas más importantes en Alemania en ese momento. En aquella época, Marx era idealista hegeliano y pertenecía al círculo de los hegelianos de izquierda, junto con Bruno Bauer y otros.[12]

Marx enfrentó dificultades financieras durante su tiempo en Berlín, lo que pudo haber afectado su asistencia a cursos y su participación en la vida estudiantil. Fue denunciado varias veces ante los tribunales universitarios por sus acreedores.

Durante su estancia en Berlín, Marx preparó su tesis doctoral, Diferencia entre la filosofía de la naturaleza de Demócrito y la de Epicuro. Aunque estudió en Berlín, presentó su tesis en la Universidad de Jena en 1841, la cual no había visitado nunca y a donde tampoco se desplazó para doctorarse: se doctoró in absentia. Las razones de esto no se conocen con certeza.

Colonia y la Gaceta Renana (1842-1843)[editar | editar código]

Artículos en la Gaceta Renana junto con Moses Hess...

París (1843-1845)[editar | editar código]

Anales Franco-Alemanes[editar | editar código]

Artículos en los Anales Franco-Alemanes junto con Arnold Ruge...

Manuscritos Económico-Filosóficos (ms. abr.-ago.1844; ed. pr. 1932)[editar | editar código]

Manuscritos Económico-Filosóficos de 1844 (escritos entre abril y agosto)...

El 28 de agosto de 1844 Marx se encuentra con Engels por primera vez en el Café de la Régence...

La Sagrada Familia (ms. nov. 1844; ed. pr. 1845)[editar | editar código]

En noviembre de 1844 escribe junto con Engels La Sagrada Familia...

Bruselas (1845-1848)[editar | editar código]

Tesis sobre Feuerbach (ms. 1845; ed. pr. 1888])[editar | editar código]

...

La ideología alemana (ms. 1846; ed. pr. 1932)[editar | editar código]

...

Miseria de la filosofía (ms. y ed. pr. 1847)[editar | editar código]

...

Manifiesto del Partido Comunista (ms. y ed. pr. 1848)[editar | editar código]

...

Colonia y la Nueva Gaceta Renana (1848-1849)[editar | editar código]

Artículo Sobre las revoluciones de 1848 y Trabajo asalariado y capital ...

Radicación en Londres (1850 en adelante)[editar | editar código]

Redacción de El Capital (1857-1867)[editar | editar código]

Manuscrito de 1857-58 o "Grundrisse" (ed. pr. 1939)[editar | editar código]

...

Contribución a la crítica de la economía política (ed. pr. 1859)[editar | editar código]

...

Manuscrito de 1861-63 (ed. pr. 1976)[editar | editar código]

En junio de 1863, Marx concluye un inmenso original compuesto de 23 cuadernos de 1474 páginas en cuarto titulado Zur Kritik der politischen Ökonomie [Contribución a la crítica de la economía política].

De este original, que a pesar de los años transcurridos sigue aún sin publicar en su totalidad, Kautsky extraerá las Theorien über den Mehrwert [Teorías sobre la plusvalía].

Redacción entre 1863 y 1865[editar | editar código]

En 1863 es cuando Marx comienza a escribir El Capital, cambiando ya el título de la obra y pasando a subtítulo "Crítica de la Economía Política". El primer borrador del Volumen 1 es terminado en el verano de 1864; sin embargo, los manuscritos de este borrador se han perdido excepto por el capítulo 6 "Resultados del proceso inmediato de producción" que permaneció inédito.

A finales de 1864, Marx pospone la redacción del Volumen 2 y comienza directamente con el Volumen 3, finalizando sus Partes de la 1 a la 3. En 1865, suspende la redacción del Volumen 3, y empieza entonces con el pospuesto Volumen 2, el cual logra terminan en su mayor parte. A finales de 1865, retoma la redacción de la segunda mitad del Volumen 3 (Partes 4 a la 7) el cual finaliza a finales del año.

Salario, precio y ganancia (disc. 1865; ed. pr. 1898)[editar | editar código]

En medio de la redacción de El Capital, nace la Asociación Internacional de Trabajadores (Primera Internacional) a la cual Marx se une convirtiéndose rápidamente en su líder de-facto. Por primera vez, luego de las revoluciones de 1848, Marx vuelve a involucrarse en el activismo político. En un discurso pronunciado por en dos sesiones (20 y el 27 de junio de 1865) del Consejo General de la Primera Internacional surge Salario, precio y ganancia.

El Capital Vol.1 (ms. 1866; ed. pr. 1867)[editar | editar código]

En enero de 1866 comienza la redacción definitiva del "primer volumen" de El Capital, aún sin tener demasiado claro su extensión y contenido puesto que inicialmente piensa incluir en él los dos primeros libros. Recién en enero de 1867 comprende que no podrá terminar el libro II y que debe limitarse a publicar el primero. El trabajo de edición de este primer libro continuaría hasta abril de 1867 y su publicación vería la luz el 14 de septiembre del mismo año.

Años posteriores[editar | editar código]

En los años posteriores de Marx, éste produjo estudios antropológicos, a pesar de las dificultades en su vida personal que le impidieron terminar gran parte de su trabajo. En 1882, Marx viajó a Argelia y escribió sobre la desigualdad y la subordinación como conceptos abominables para todos los verdaderos musulmanes.[13]

Publicaciones póstumas[editar | editar código]

...

Obras[editar | editar código]

Véase también: Portal:Obras de biblioteca de Karl Marx & Friedrich Engels

- Gymnasium de Tréveris:

- Universidad de Berlín:

- 1837 nov 10: Carta al padre

- 1837: Escorpión y Félix

- 1841: Diferencia de la filosofía de la naturaleza en Demócrito y en Epicuro

- Etapa pre-materialista

- Surgimiento del materialismo dialéctico

- 1844: Sobre la cuestión judía (en los Anuarios Franco-Alemanes)

- 1844: "Introducción" a la Contribución a la crítica de la filosofía del derecho de Hegel (en los Anuarios Franco-Alemanes)

- 1844: Crítica a la filosofía del Derecho Público (o del Estado) de Hegel, también llamado Manuscrito de Kreuznach

- 1844: Glosas marginales al artículo "El rey de Prusia y la reforma social. Por un prusiano"

- 1844: Manuscritos económico-filosóficos de 1844

- 1845: Tesis sobre Feuerbach

- 1845: La sagrada familia (con Engels)

- 1847: La crítica moralizante y la moral crítica

- 1847: La miseria de la filosofía

- 1848: Manifiesto del Partido Comunista (con Engels)

- Obras materialistas tempranas

- 1849: Trabajo asalariado y capital (en Nueva Gaceta Renana)

- 1850: La lucha de clases en Francia (1848-1850) (en Nueva Gaceta Renana. Revista político-económica)

- 1850: Mensaje del Comité Central a la Liga de los Comunistas (con Engels)

- 1852: El 18 de brumario de Luis Bonaparte

- 1853: La dominación británica en la India

- 1853: Futuros resultados de la dominación británica en la India

- 1854-57: La España revolucionaria

- Redacción de El Capital

- 1857-58: Elementos fundamentales para la crítica de la economía política (Grundrisse) o Manuscrito de 1857-58

- 1859: Una contribución a la crítica de la ecomomía política

- 1861-63: Manuscrito de 1861-63 (Contiene Teorías de la plusvalía)

- 1863-65: Volumen 1 (perdido, excepto por el capítulo 6 "Resultados del proceso inmediato de producción" que permaneció inédito). Luego procede a escribir el Volumen 3 (Partes de la 1 a la 3), el Volumen 2, el Volumen 3 (Partes 4 a la 7).

- 1865: Salario, precio y ganancia

- 1867: El Capital Vol. I

- Herr Vogt

- La guerra civil en USA (con Engels)

- (...)

Referencias[editar | editar código]

- ↑ Lenin (1913-03) Tres fuentes y tres partes integrantes del marxismo

- ↑ Saltar a: 2,00 2,01 2,02 2,03 2,04 2,05 2,06 2,07 2,08 2,09 2,10 Michael Heinrich (2021). Karl Marx y el nacimiento de la sociedad moderna. Biografía y desarrollo de su obra. Volumen 1: 1818-1841 (Karl Marx und die Geburt der modernen Gesellschaft: 1818-1841). Akal. [LG]

- ↑ “In 1794, Trier was occupied by French troops. Revolutionary France had not only beaten back the monarchist powers but had made considerable territorial conquests. [...] After Napoleon’s failed Russian campaign, French rule ended. In 1815, at the Congress of Vienna, Catholic Trier, along with the Rhineland, was awarded to Protestant Prussia.”

Michael Heinrich (2019). Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work (pp. 39-40). Nueva York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-735-3 [LG] - ↑ “In 1819, Trier had hardly more than 11,000 inhabitants; furthermore, about 3,500 soldiers were stationed in Trier (Monz 1973: 57). This was not an especially large population, even if one takes into consideration that back then most people lived in the countryside and cities had far fewer inhabitants than today. [...] The Trier in which Marx grew up was characteristically rural; it had only two main streets, the rest of the town consisting of side alleys and little streets.”

Michael Heinrich (2019). Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work (pp. 39-40). Nueva York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-735-3 [LG] - ↑ “Parents Heinrich (1777–1838) and Henriette (1788–1863) had married in 1814. Both came from Jewish families that converted to Protestant Christianity. Karl Marx was baptized on August 26, 1824, along with his then six siblings. At this point, his father had already been baptized; the exact date, however, is not known. His mother was baptized a year later, on November 20, 1825. On the occasion of the baptism of her children, according to the entry in the church register, she wanted to wait with her own baptism out of consideration for her still-living parents, but she wanted her children to be baptized.”

Michael Heinrich (2019). Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work (p. 35). Nueva York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-735-3 [LG] - ↑ “Marx’s father was a well-regarded lawyer in Trier, and his income allowed his family a certain affluence. Both the house on Brückengasse (today Brückenstraße), which the family rented and in which Karl was born,16 as well as the somewhat smaller, but centrally located house on Simeonstraße that the family purchased in the autumn of 1819 and in which young Karl grew up, were among the better bourgeois homes of the city. (p.35)

[...]

The center of social life in Trier was the Literary Casino Society (Literarische Casinogesellschaft) founded in 1818. Its statutes determined its purpose to be “maintaining a reading society connected to an association location for the convivial enjoyment of educated people” (quoted in Kentenich 1915: 731). In the Casino building, completed in 1825, there was a reading room that also contained several foreign newspapers. Balls and concerts, and on special occasions banquets, were regularly held (see Schmidt 1955: 11ff.). The sophisticated bourgeois stratum and the officers of the garrison belonged to the Casino. Karl’s father, Heinrich Marx, was one of the founding members. Similar societies, often with the same name, also arose at the end of the eighteenth and beginning of the nineteenth century in other German cities; they were important focal points for the emerging bourgeois culture. Critique of existing political conditions was also articulated here. (pp. 41-42)”

Michael Heinrich (2019). Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work (pp. 35-42). Nueva York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-735-3 [LG] - ↑ “Professional success was also reflected in a certain level of affluence. In 1819, Heinrich Marx was able to buy a house on Simeonstraße. According to the tax information evaluated by Herres, Heinrich Marx was assessed in 1832 as having an income of 1,500 talers annually, thus belonging to the upper 30 percent of the Trier middle and upper class that had a yearly income of more than 200 talers. Since this middle and upper class only comprised around 20 percent of the population, the Marx family, in terms of income, belonged to the upper 6 percent of the total population. With this income, the family was also able to accumulate a certain level of wealth, owning multiple plots of land used for agriculture, among which were vineyards. For wealthy citizens of Trier, ownership of vineyards was a popular retirement provision. The Marx family also employed servants. In the year 1818, there was at least one maid; for the years 1830 and 1833, “two maids” are documented.”

Michael Heinrich (2019). Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work (pp. 67-68). Nueva York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-735-3 [LG] - ↑ “The towering presence of the Trier gymnasium was its director of many years, Johann Hugo Wyttenbach (1767–1848). He was also an archaeologist and founder of the Trier city library. In 1804, Wyttenbach was already director of the French secondary school; he remained director of the gymnasium until 1846. His thinking was strongly influenced by the Enlightenment; in his earlier years, he was an adherent of the French Jacobins. He maintained his liberal and humanistic ethos even under Prussian rule.”

Michael Heinrich (2019). Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work (p. 97). Nueva York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-735-3 [LG] - ↑ “When the young Karl started gymnasium in 1830, Wyttenbach was sixty-three years old. Most teachers were considerably younger, and as can be gleaned from the fragmentary information of the surviving records, at least a few of them had rather critical attitudes toward the reigning social and political conditions and were observed with distrust by the Prussian authorities.

First and foremost to be named in this regard is Thomas Simon (1793– 1869), who taught French to Karl at the Tertia level. [...] He had “turned toward the concerns of the poor, neglected people,” since as a teacher he had seen daily that “it was not the possession of cold, filthy, minted money that makes a human being a human being, but rather character, disposition, understanding, and empathy for the weal and woe of one’s fellows” (quoted in Böse 1951: 11). In 1849, Simon was elected to the Prussian house of representatives, where he joined the left. His son, Ludwig Simon (1819–1872), also attended the gymnasium in Trier and took the Abitur exams a year after Karl. [Ludwig] was elected to the national assembly in 1848. As a result of his activities during the revolutionary years of 1848–49, the Prussian government brought multiple legal proceedings against him and convicted him in absentia to death, so that he had to emigrate to Switzerland.

Heinrich Schwendler (1792–1847), who taught French to Marx at the Obersekunda and Prima levels, was suspected in 1833 by the Prussian government of being the author of an insurgent leaflet; he was accused of “poor character” and of “familiar relationships to all the fraudulent minds of the local city.” In 1834, a ministerial commission warned of the “pernicious orientation” of Simon and Schwendler, and in 1835, the provincial school council regarded his dismissal as desirable, but could not find a sufficient reason (Monz 1973: 171, 178).

Johann Gerhard Schneeman (1796–1864) had studied classical philology, history, philosophy, and mathematics; he published numerous contributions on the archaeology of Trier. At the Tertia and Obersekunda levels, he taught Karl Latin and Greek. In 1834, Schneeman also participated in the singing of revolutionary songs at the Casino and was interrogated by the police as a result.”

Michael Heinrich (2019). Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work (pp. 98-99). Nueva York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-735-3 [LG] - ↑ “Ludwig von Westphalen and Heinrich Marx had annual incomes of 1,800 and 1,500 taler, respectively.”

Michael Heinrich (2019). Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work (p. 45). Nueva York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-735-3 [LG] - ↑ “Eleanor also discloses that the young Karl was intellectually stimulated primarily by his father and his future father-in-law, Ludwig von Westphalen. It was from the latter that he “imbibed his first love for the “Romantic” School, and while his father read him Voltaire and Racine, Westphalen read him Homer and Shakespeare.” The fact that Marx dedicated his doctoral dissertation rather emotionally to Ludwig von Westphalen in 1841 demonstrates how important the latter was to him.”

Michael Heinrich (2019). Karl Marx and the birth of modern society: the life of Marx and the development of his work (p. 36). Nueva York: Monthly Review Press. ISBN 978-1-58367-735-3 [LG] - ↑ Lenin (1914). Carlos Marx. (Breve esbozo biográfico, con una exposición del marxismo) marxists.org link

- ↑ Vijay Prashad (2017). 'Eastern Marxism' en Red Star over the Third World (p. 83). [PDF] Nueva Delhi: LeftWord Books.